In many ways, German writer and artist Else Lasker-Schüler appeared to her contemporaries as a being who had fallen out of time. In early 20th century Berlin, she stalked the streets of the frantically modernising city dressed as “Princess Tino” or the “Prince of Thebes”, and much of her poetry, prose and drawings of this era sprang from a timeless, notional “Orient” of her imagination. Fusing Jewish and Muslim traditions, the Pentateuch and 1001 Nights, she populated her fantasy landscape with associates in diaphanous fictional disguise, watched over by a crescent moon and a six-pointed star.

But Else Lasker-Schüler was also very much a creature of her age. When she returned to visit her beloved home of Wuppertal in the early 20th century, she was much taken by the new hanging monorail system, the “Schwebebahn” – a confrontingly alien conveyance even today – which hovered above the industrial city’s river. She was also an early, devoted fan of cinema, and wrote a film treatment (sadly never developed) for one of her stories before the First World War. And of course she was a key exponent of Expressionism, which for much of the first three decades of the 20th century was a – and for much of that time the – dominant force in avant-garde German arts and letters, and indeed film. While Lasker-Schüler’s belief in the redemptive power of romantic and sensual love may have been atypical among the Expressionists, she shared in their radical rethinking of literary means.

Although success was always a relative concept for Lasker-Schüler, with accolades sporadic and rarely accompanied by material security, 1920 began with her on something of a creative high. Her major dramatic work Die Wupper had just been staged for the first time to considerable acclaim, ten years after it was written. Art dealer Paul Cassirer was in the midst of publishing a complete set of her written works, each of the ten volumes with a cover image by Lasker-Schüler herself. These and other graphic works, meanwhile, were exhibited in a major show in Munich in early 1920, and the Nationalgalerie in Berlin also acquired a number of her drawings. Lasker-Schüler was also giving readings and lectures throughout Europe.

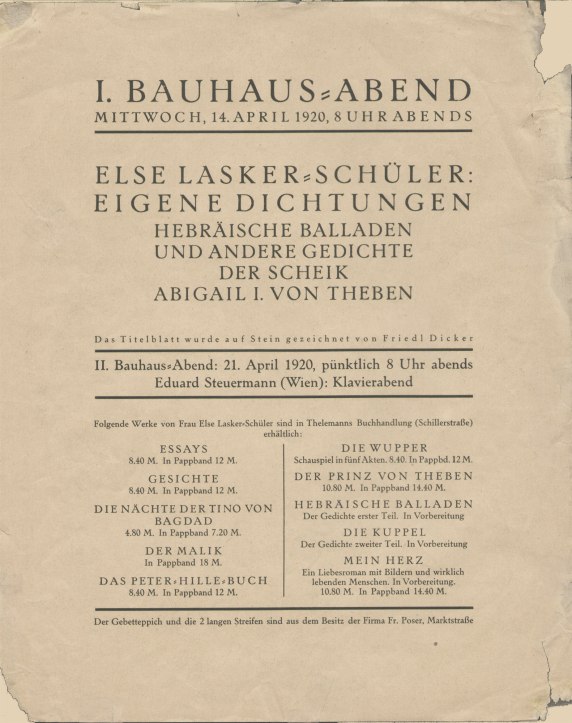

One reading stands out in particular: her appearance at the first of a series of “Bauhaus Evenings” at Walter Gropius’s design school in Weimar, which took place 100 years ago today.

While Lasker-Schüler was always attuned to new creative energies, the mere presence of a figure indivisibly associated with raw, unruly Expressionism at the high temple of clean-lined rationalism may seem odd at first glance. But, as I mentioned in discussing a range of books released to mark the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus movement last year, Walter Gropius and his associates were never as wholly devoted to cold logic as their reputation suggests.

The series of “Bauhaus Evenings” which would later encompass lectures and readings by visionary architect Bruno Taut, messianic preacher Ludwig Christian Haeusser, cultural catalyst Harry Graf Kessler, as well as chamber music recitals, began on 14 April 1920 with a spirited reading by Else Lasker-Schüler. It was publicised with a poster by Friedl Dicker, one of the numerous women artists and designers at the early Bauhaus, who later gave secret art lessons to children in Theresienstadt concentration camp before she was transferred to Auschwitz and murdered.

The 2019 German television series Die Neue Zeit focussed on the women of Bauhaus, and framed the liberated Lasker-Schüler’s appearance as a daring affront to the traditionalist forces which were by no means extinguished in Weimar. The small German city had just hosted the constitutional conference that would in time see its name attached to the republic it created, first in contempt, then pity, later still with an aura of dark, doomed glamour.

According to one report, Lasker-Schüler’s performance was apparently lit by “a single candle”, although this seems somewhat unlikely. She recited, or rather performed a selection of her lyrical works, and was met with both rapturous applause and disdainful silence. The factions of the audience are represented in Die Neue Zeit by Dörte Helm, a real-life student at the school who is depicted hatless, I repeat – hatless, and the very much hatted conservative aristocrat artist (and animal psychologist) Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven, who was bitterly opposed to Gropius’s takeover of Weimar’s art school (and definitely not to be confused with the “Dada Baroness”, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven). This polarised response was hardly atypical; even individuals exhibited mixed feelings when confronted with Else Laskser-Schüler’s uncompromising artistic persona. One of her readings in Munich later that year was attended by a young Bertolt Brecht, who found her poems “good and bad … excessive and unhealthy, but wonderful in isolation” (adding “The woman is old and spent, flabby and unappealing” – the charmer!).

Lasker-Schüler continued to make new contacts among the vanguard of new creators. In summer 1920 her work appeared in the “Erste Internationale Dada-Messe”, the first international Dada art fair, at the canalside Galerie Dr. Otto Burchard in Berlin. What’s more, it was a collaboration with Otto Dix – arguably the foremost representative of the ascendant movement Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity).

In 1920 Lasker-Schüler’s thoughts turned to film once again, just as German cinema was entering a period of unparalleled creative vitality. She encouraged her handsome son Paul, a promising artist in poor health, to seek work in one of Berlin’s booming film studios. This plan appears to have taken an unfortunate turn when he made a (failed) pass at Leni Riefenstahl, but Else remained in the grip of film mania, even approaching director Ernst Lubitsch about appearing in one of his films, although nothing came of it.

But just across the narrow canal from the gallery that hosted the Dada exhibition was a building that represented a different, darker strand of Lasker-Schüler’s fate (see “Else Lasker-Schüler’s Berlin”). It housed a studio occupied by Palestinian-Jewish artist Jussuf Abbo, whom Lasker-Schüler met around this time. He had set up a Bedouin tent in the space, a feature that naturally appealed to her sense of exoticism, but his studio also became a refuge. As the 1920s wore on, Paul’s health worsened, and as the expense of his treatment drained Else’s slender means, the two moved in with Abbo. Else largely withdrew from public life to attend to her son – to no avail. Paul Lasker-Schüler died in 1927, and although his mother lived until 1945, she never truly recovered.

Further reading

The Son of Lîlame

Evening Colours

Places: Nollendorfplatz

Else Lasker-Schüler | Theben

Strange Flowers guide to Berlin, part 3 and 4

Dress-down Friday: Else Lasker-Schüler

D’ac!

Oh, I forgot about Die Neue Zeit! I hope it is available here soon. Great post!

Thanks James!

Pingback: Ludwig Christian Haeusser, 1920 | Strange Flowers

Pingback: Dear King of Holland | Strange Flowers

Pingback: Three Prose Works | Strange Flowers