Few dates embody the “decline” inherent in the original French definition of décadence more than April 26, 1895, signalling as it did the fall of two of the figures most readily associated with capital ‘D’ Decadence. One hundred and twenty years ago today, Oscar Wilde was facing the first day in his trial for gross indecency, the start of the precipitous decline which would end five years later in his premature death. On the same day, Count Eric Stenbock expired in a fit of pique, gripped by madness, alcoholism and addiction, aged just 35.

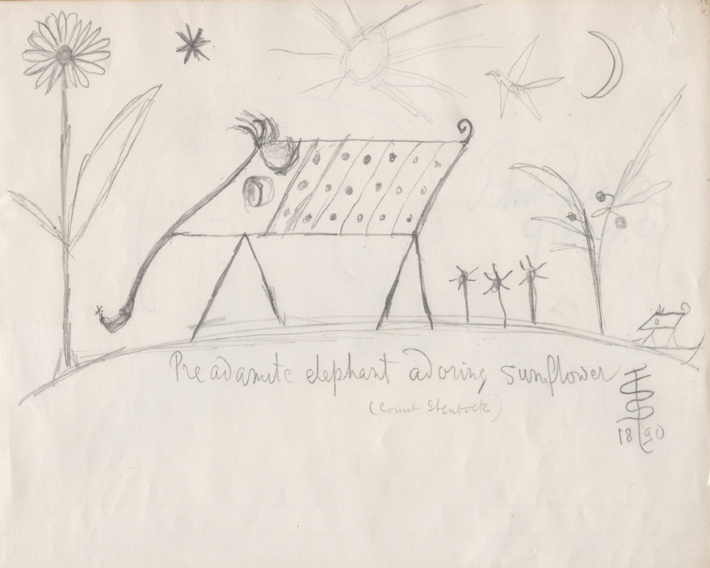

In his life and afterlife Stenbock never attracted a fraction of Wilde’s renown, but no-one in the present day has done as much to change that as David Tibet. Recently when I posted a news report concerning the restoration of Stenbock’s ancestral seat in Estonia, David himself stopped by to comment. His interest in Stenbock is typical of his boundless curiosity. As prolific as he is with his group Current 93 and numerous other musical and artistic projects, David’s manifold ancillary interests are no mere sidelines, and he has brought passion and scholarship to subjects as diverse as Outsider artist Madge Gill and Coptic theology. Between 1996 and 2004, his Durtro Press imprint published more or less everything the Count wrote, works which were otherwise impossible to come by. During this period Current 93 issued the mesmerising sonic séance Faust, based on Stenbock’s story of the same name. The summit of David’s Stenbockian activities will be an anthology of the Count’s collected works, which will include numerous previously unpublished pieces.

David has generously agreed to answer some questions to mark this auspicious anniversary. It’s a rare pleasure to hear someone talk so knowledgeably about a beloved figure.

James J. Conway: You’ve been engaged with the life and work of Eric Stenbock for many years now. What was your first encounter with the Count, and what was it about him that captured your imagination?

David Tibet: I think the first time I heard of Eric was in 1979 when I read Francis King’s popular biography, The Magical World of Aleister Crowley. Obviously I bought it because I was interested in Crowley, but King writes somewhere when he’s talking about the people that had influenced Crowley, or were perhaps aesthetic bedfellows, “Stenbock made an attempt to understand his own homosexuality in terms of traditional occultism, eventually coming to view his condition as an aspect of vampirism and lycanthropy, torn between Catholicism and diabolism, he died, deluded that a huge doll was his son and heir, in 1895.”

In the 1990s I started collecting M. R. James first editions and became interested in other supernatural fiction of a similar antiquarian bent to M. R. James. I was having lunch with Tim d’Arch Smith and [he] said to me, “have you ever read Stenbock’s Studies of Death?”. I vaguely knew the title and then I remembered what I’d read about Stenbock. Tim said that Edwin [Pouncey], our mutual friend from Sounds – Savage Pencil – had a copy and might be willing to sell it. He did and I took it home, laid on the couch, read it, and became totally obsessed by Stenbock. Edwin said to me, “Studies of Death is rare but the three books of poetry are impossibly rare”, and that I would never get them; even the British Library didn’t have them all. But the obsession became so strong that I determined I would get these books. I also bought [John] Adlard’s excellent biography [Stenbock, Yeats and the Nineties] , and that set me on the quest. It really took me over and I just followed up every possible lead I could.

Perhaps I’ve always been drawn to people whose work I feel has been unjustly overlooked, people like Louis Wain, Tiny Tim, whose work I love but had been forgotten more or less, Shirley Collins, such a beautiful person, such a beautiful voice and forgotten for a long time. Also I thought of The Quest for Corvo. There wasn’t much beyond Adlard and a few other bits and pieces, Christmas with Count Stenbock, the few mentions in Ernest Rhys’s autobiographical writings. But I kept thinking about Enoch Soames in Max Beerbohm’s book where Enoch Soames says “I’m a diabolist, a Catholic diabolist.” So it also linked up with other things that have always fascinated me: grimoires, Catholicism, diabolism; Huysmans and his À Rebours and Là-Bas were huge influences on me in the early years of Current and they’re still books that I love.

JJC: John Adlard describes his subject as a “pervert” who “achieved almost nothing”, Arthur Symons called him a “failure”, while a contemporary review of his work declared “it must be a parody”. Do you have any sympathy for their views?

DT: Odd that Adlard called Stenbock a pervert. Adlard, I know was heterosexual and married, but he obviously had a great fondness for this pervert. But it seems even in 1969 a peculiarly blunt moral judgment. Symons did call him a failure although of course Symons in the period you refer to had been through a massive nervous breakdown and mental collapse. The contemporary view declaring “it must be parody” – that’s very much High Victorian Muscular Christianity in play I think. One of the things I love about Stenbock’s work is, for “the king of the Decadents” his writing style is remarkably undecadent. I think he was influenced by Balzac, who he loved; it was actually quite a plain, unornamented style. His poetry is sometimes very mauve, very purple. I don’t have any sympathy but I like the fact that they gave those views, because they were giving views on someone who was barely known. So God bless Eric – some people noticed him while he lived.

JJC: Stenbock’s first book of poetry came out in 1881, and examined themes of illness, decay and morbidity before Decadence was even established as a literary movement. He actually owned a hothouse in 1885, only a year after Huysmans published À Rebours. Do you think Stenbock deserves more recognition as an innovator in developing Decadent themes, both in his work and in his life?

DT: People come to his work expecting something incredibly Decadent, but if you look at the stories in Studies of Death, which is the one that people had the most access to, they’re not terribly Decadent. “True Story of a Vampire” is certainly Decadent. If you look at “Faust”, which I published for the first time, that is a masterpiece of Catholic, diabolist Decadence. Hopefully when I put out my edition of the collected works of Stenbock it will make things a lot easier and people can make their own mind up about him. When I first read Stenbock I fell in love with him. I fall in love quite easily with writers and poets and artists, especially when they’re no longer living and unable to disappoint me. Stenbock means so much to me, his work means so much to me – his success and his failure.

When I was trying to find the last of the first editions, the only one I didn’t have at the time was The Shadow of Death and I was on the phone with Martin Stone, one of the best book dealers, and a member of the Pink Fairies, one of my favourite bands. He had a lead on a copy and every time he rang up about it, a blue butterfly would come into my room from outside and I still believe that was Stenbock coming in the form of a butterfly, about which he often wrote. I believe that Stenbock was looking down on me and wanted me to help bring him back to public awareness or at least do the best that I could. I think Stenbock’s time will come. He’s a moving person; I met a lot of kindness in my search for his works. I feel I was in the right place at the right time. And it had always surprised me that no-one else had looked into him much since Adlard. For example, Adlard mentions all these papers at I Tatti [the Florence villa inhabited by Bernard Berenson and Stenbock’s childhood friend Mary Berenson, née Smith], and he says they’re of no literary value, or something dismissive like that, but nobody else had been there to look at them.

JJC: Stenbock’s bedroom in Estonia was notoriously adorned with a pentagram, he had some kind of shrine in his London house, but he was also conspicuously Catholic. How would you characterise Stenbock’s beliefs?

DT: I went to Stenbock’s bedroom at Kolk. Unfortunately there was no pentagram there any more although there was some nice blue-green wallpaper, although whether it was original or not, who knows. Again the shrine – it’s just difficult to know what the truth is. There’s traces of the usual Decadent pantheism and classical religion in Stenbock’s poetry, especially, and a heavy Catholicism. I have a letter in which his step-father [is] writing to his uncle; says “Disastrous news: Eric has converted to Catholicism.” And he goes on to say that “I hope in the fullness of time when Eric matures he will choose a less ridiculous religion”. He’s also suggesting to the uncle that they get Eric to join the Tsar’s army. So I think his family were pushing him to be more martial and masculine but realised they were swimming against Stenbock’s tide.

JJC: You commented that there is often no proof, positive or negative, for the more outlandish tales about the count, like the life-sized doll he claimed as his son.

DT: A couple of Stenbocks that I’ve met – I know three Stenbocks – don’t know where it comes from, they don’t believe it’s the case. I hope it’s the case, it’s a fantastic story and it’s so associated with Stenbock. Let’s just say it is the case but there’s no proof of it and I couldn’t find any papers which mentioned it, including diaries connected to Stenbock by people who knew him.

JJC: There’s also a story that Oscar Wilde visited Stenbock’s house…

DT: The meeting at Stenbock’s house when Wilde lights his cigarette from the flame in front of the bust of Shelley – again a fantastic story. Timothy d’Arch Smith thinks it isn’t true and I’ve never seen it anywhere else. Again it doesn’t mean it’s not true. Yeats met Stenbock and there’s Yeats’ record of his meeting with Stenbock [a thinly fictionalised account in The Speckled Bird, which David kindly brought to my attention]. There’s no record that Wilde met Stenbock. I always check out Wilde indices to see if there is any mention of Stenbock, but I never see them. Stenbock did know Beardsley well and would buy Beardsley drawings.

JJC: Stenbock’s brand of arch, macabre Decadence will always appeal to a select temperament, but do you think the Count’s profound awareness of his own mortality and the sense of dissolution at the end of the 19th century have any resonance for a broader public in the present day, when we seem hell-bent on engineering our own decline?

DT: I think that people who are hell-bent on engineering their, as well as our own decline, are not going to take the time to read or even consider the meaning of three slim volumes bound in vellum of Decadent, tortured, vampiric, homosexual poetry. Maybe they should – I think there’s a message there for all of us. Stenbock still seems to be a great outsider. Even if you look at d’Arch Smith’s beautiful book Love in Earnest on the Uranians – an absolutely fantastic book, I can’t recommend it enough – even there he stands out, not one of the crowd, just ploughing his own strange furrow, somewhere between despair and ecstasy. He ended up in despair. Maybe there’s the resonance for the broader public in the present day: despair.

JJC: You’ve reissued Stenbock’s work in the past, including unpublished material. I know a lot of people are looking forward to the forthcoming anthology. What fresh discoveries await us?

DT: There’s a lot of unpublished material in my edition, lots of letters, there’s a fantastic unfinished – or incomplete – lost civilisation story. There’s the famous almanac with the sacred days of the week and the colours that the Idiot Club [a group formed by the young Stenbock and Mary Berenson along with two of her siblings] wrote, some photographs that people haven’t seen before. Not a huge amount of short stories that haven’t already been published. There’s poems for children. I’ve been working on it for so long and I wish it had been finished by now. Of course it’s a hobby of mine and not my main work. I hope to get it out for the end of this year.

Wonderful interview. Stenbock is new to me so I am looking forward to the anthology. Hopefully i will have finished up that last Corvo book by then!

“Some people noticed him while he lived.” Oh dear, and after all that work at public eccentricity… Was he not as shameless a social climber as his peers, is that part of why he’s not better known?

Fabulous interview, can’t wait for the book!

I see him as the private piano recital to Wilde’s grand opera, and I suspect for all his apparent attention seeking he preferred it that way. (Aside: I’m missing Deviates Inc.!)

Ooh, this was just delicious!

According to The National Portrait Gallery website the chap on the right of the Idiot Club photo is writer Logan Pearsall Smith, who went on to produce The Youth of Parnassus in the year of Stenbock’s death.

Did the Idiot Club serve any useful purpose or was it just a bit of youthful fun I wonder?

Great Stuff. Thanks both.

I’ve been following David Tibet and Current 93 and related musical projects as a quiet and humble fan and sympathetic spirit in the wondrous ineffable realm, or realm which bursts categories and recombines elements into new fabulous entities of creation, for nearly 25 years now. Not only gifted and original as a poet and performer but also a generous and appreciative human being Mr. Tibet is, as anyone who reads his liner notes might discover. I recall when I was a young vanilla and square college student hearing Dogs Blood Rising, Nature Unveiled, and Imperium for the first time, and being disturbed magnificently by the obscure occult power of those works. The listening experience moved my imagination into what seemed to be forbidden places, but it connected with what I secretly felt inside, and I was thrilled. I was brought up a Catholic too, and definitely feel the lure of the diabolical, the curious delight in perversity which exists in heady and perfumed or incensed mixtures, exotic and strange, in the shadows of those things considered holy. I still get into certain moods where I like listening to those earlier works. Current 93’s “Faust” seems to harken back to those earlier works, though it’s more restrained, maybe more cinematic in its soundscape, music for the black & whites and gradations of gray of the silent film, music for the imagined animation of the existent photos of Stenbock. The blurred image of Stenbock’s face on the album cover, framed up close, could at a glance be taken for Tibet’s own face. It’s what I thought when I first saw the cover, before I knew anything about the album. There’s a meeting of essence in that blurriness, in that superimposition if you will, a looking at each other through the mirror, Stenbock now on the side of Death and Tibet still alive and seeing through it to his friend from another time. It’s too bad Stenbock and David Tibet, he with his motley assortment of fascinating friends, never met each other in reality. I wonder if it might have helped save Stenbock, spurred him on creatively away from self-destruction and damnation and more toward total self-acceptance and redemption toward which it appears Tibet is now going as he has grown older. I wonder if Tibet on some level regards Stenbock not only as a precursor, a brother in spirit as background formative influence, but as he himself has grown older than 35, Stenbock’s death age, even as a kind of son. A prodigal son.

Polsh edition of “FAUST”

– http://zoas.pl/index.php?MENU=news&IDA=25&OD=0

Pingback: 16 books for (what’s left of) 2016 | Strange Flowers

Pingback: Eric Count Stenbock – A Character (James J. Conway, The quest for Stenbock) | Frank T. Zumbachs Mysterious World

Durtro Press editions reach astronomical prices on AbeBooks. I got a French translation of Studies of Death for eleven euros plus four euros postage.

Pingback: 18 books for 2018 | Strange Flowers

Pingback: Eric Stenbock: Drinking song | Agapeta

Pingback: Viol d’amor | Strange Flowers

Pingback: Secret Satan, 2019 | Strange Flowers