Rosa Bonheur was born two hundred years ago today. She would go on to be the most famous and successful woman artist of the 19th century, dressing in men’s clothing, smoking cigars, riding astride and living openly with female partners. Looking back, it is remarkable how early these outcomes manifested, with Bonheur’s huge talent and strength of character forged by both a sympathetic environment and childhood tragedy, and how each phase can be read in images of, by or associated with her.

Raymond (or Raimond) Bonheur (1796-1849) was an early 19th-century painter, not particularly successful (here in a self-portrait); he met his wife Sophie, née Marquis, when he gave her art lessons.

Their daughter Rosa was born in Bordeaux on 16 March 1822. Here we see Raymond Bonheur’s tender depiction of his baby daughter.

This is Monsieur Bonheur’s later portrait of his daughter Rosa, now aged four. She has a Punch doll and a pencil; as a child she would imitate her portraitist father by sitting her doll in a chair and drawing its likeness (dolls will recur in this story). Rosa’s sister and her two brothers would also grow up to be artists. Vanishingly few male artists of the time would have considered art a vocation fit for their daughters. Simply getting training, let alone establishing a career in art, was all but impossible for women at the time. So what was different about the Bonheurs?

Comte Henri de Saint-Simon (here in a portrait by Hippolyte Ravergie) was a visionary reformer whose politico-religious Saint-Simonian movement embraced an early form of socialism as well as biblical Christianity. Saint-Simon himself died in 1825, but a few years later Raymond Bonheur – born Jewish – pledged himself (and by extension his family) to his teachings. Crucially, the movement supported equal opportunities for girls and boys, particularly in education. After some initial resistance, Raymond began instructing his daughter in art.

Sophie (here with Rosa and her brother Auguste in a study by Raymond) gave piano lessons to support the family. While Rosa was still a child the family moved to Paris; Sophie suffered from her husband’s idealistic whims, especially when he abandoned the family to live in a Saint-Simonian community. Rosa was just eleven when her mother died of exhaustion, a traumatic break which appears to have instilled in her a drive to succeed and find meaning in her life, and to avoid marriage.

Nathalie Micas (here in a later portrait by Rosa Bonheur) had been a sickly child, and in 1836 her parents commissioned Raymond Bonheur to paint a portrait of the twelve-year-old in the expectation that she wouldn’t live much longer. So it was that she came into contact with Rosa, who was 14. The two became inseparable.

The widowed Raymond Bonheur joined a revival of the Knights Templar and enlisted his daughter as well (seen here wearing the uniform as an adult). An unruly child, she laid waste to her school’s flower beds with the wooden sword that came with the ceremonial robe.

Rosa Bonheur began selling her works as a teenager; she exhibited this work at the Salon in Paris at just 19. Her enormous talent, along with her marked preference for zoological subjects, were apparent early on. Her father had remarried and visiting her stepmother’s family in the Auvergne awakened her love for the bucolic. Her animal paintings were not delicate or idealised, instead honouring the presence and dynamism of her subjects, as well as their distinguishing individual characteristics.

The Horse Fair was Bonheur’s most famous canvas. To deflect unwelcome attention in the overwhelmingly masculine settings in which she sought her subjects – fairs, abattoirs, markets – she took to wearing trousers. She was now approaching the peak of fame; in 1856 Queen Victoria requested that Bonheur present The Horse Fair to her in person. That same year, Anna Klumpke was born in San Francisco.

Academician Édouard Dubufe painted Bonheur in 1857; in the original pose he had her leaning against a table; she thought this too banal and actually painted in a bull under her arm. She was particularly drawn to Salers cows – robust, proud, curious and elegant yet shy of attention, much like Bonheur herself.

While Dubufe’s portrait shows a feminine Bonheur, she was now a card-carrying cross-dresser; literally – this is the 1857 permit that Rosa Bonheur received from the Parisian police to wear men’s clothes. It was a permit also issued to Rachilde, George Sand and Jane Dieulafoy (there was no equivalent for cross-dressing men). Bonheur gave various reasons why she preferred men’s clothes, often emphasising comfort, practicality and the urge to be inconspicuous. What is less apparent is why Bonheur dressed not like a man of her age but in a late 18th-century style. Perhaps it was an oblique tribute to her father and his attachment to the ideals of the French Revolution? In any case, she would switch between fashion codes for the rest of her life.

Bonheur’s unconventional attire was no barrier to her fame; in fact she embodied a new kind of international celebrity. A doll was made with her features, often dressed in men’s clothes; it was sometimes known as the “German Gentleman”, and bore a remarkable resemblance to Bonheur père. It became a highly popular toy for girls, including the young Anna Klumpke.

Rosa Bonheur and Nathalie Micas remained together for over 40 years; their fathers had blessed their union on their respective deathbeds.

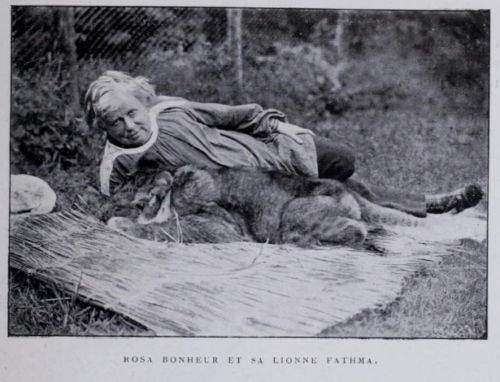

Bonheur bought a chateau and there the two women kept a menagerie of animals for Rosa to paint; not just domestic farm animals but lions and monkeys as well; one monkey would imitate Rosa painting, just as Rosa had once imitated her father. While Rosa painted, Nathalie attended to her inventions, including a railway brake which she patented in 1863. It was evidently a promising breakthrough, but it was not until a man adapted it slightly and presented it under his own name that it was accepted for further development.

Rosa jotted this sketch of Prussian soldiers down in 1850 when she visited Prussia itself (“a beastly country”) but would encounter its army again twenty years later during the Franco-Prussian war, when she was intent on forming a citizens’ militia. When she received a letter of safe conduct from Prussian Prince Friedrich Karl she tore it up.

Anna Klumpke, now an art student, arrived in Paris in 1877 with her mother, who encouraged Anna’s education.

Rosa painted Buffalo Bill in 1889, the year Nathalie Micas died, and the year that Anna Klumpke – fascinated by Bonheur, the figure from her childhood doll – first met the older artist. The two women became close and when Anna returned to the US in 1891, Rosa requested that she find some authentic buffalo grass for her to draw, sending her on something of a chivalric quest. Anna returned to France in 1895 and eventually asked Rosa if she could paint her portrait.

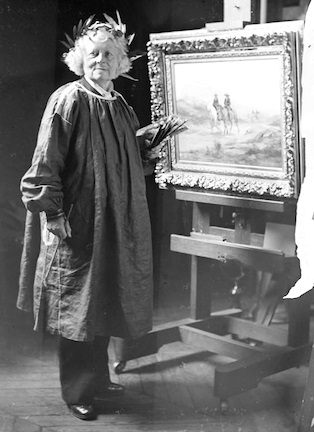

Anna Klumpke painted this portrait of Rosa Bonheur in 1898 (with the Légion d’honneur she received in 1865, the first woman artist to be so honoured). During the sitting the two fell in love.

Anna and Rosa and resolved to dedicate their lives to each other.

Anna fashioned a wreath of laurel for Rosa; she was buried with it (alongside Nathalie) when she died in 1899. Anna devoted the rest of her life to preserving Bonheur’s legacy, and produced a biography of Bonheur from notes that the artist had dictated before she died. When she died in 1942 she was buried alongside Rosa and Nathalie.

The 1900 edition of the academic journal, Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen (Yearbook for Sexual Intermediaries), edited by Magnus Hirschfeld, carried an image of the recently deceased Rosa Bonheur as a frontispiece. The caption confidently proclaims her to have been a “mentally and physically pronounced type of a sexual intermediate stage”; at the time Hirschfeld often conflated same-sex attraction (and transgender identity) with intersex characteristics. In any case, here we see queer history being written in near-real time.

It is difficult to convey the scale of fame that Rosa Bonheur enjoyed at her peak. If her name excites less recognition now it is not for want of accomplishments, it merely reflects declining interest in the kind of genre painting in which she excelled. Rosa Bonheur posthumously inspired a pet cemetery in Maryland in 1935, but it is only in recent years that she has come back into focus. Her evocative name is attached to a string of bars in Paris and her chateau is now a museum dedicated to her work, which in 2020 also hosted a festival of music by women composers. Catherine Hewitt’s biography Art is a Tyrant from the same year reintroduced Bonheur to English-speaking readers while this year brings the mid-length film Rosa Bonheur, Dame Nature, the inevitable Google doodle and a stamp bearing one of her lion images.

The shame is that there are homophobes in France who are involved with this exhibit trying claim that Rosa was heterosexual. This is refuted in Suzette Robichon’s 2012 book in French on Rosa’s will. Telling lesbian’s real stories is dangerous.

It’s hard to believe that kind of erasure is still going on in 2022. I know sometimes there’s some guesswork and reading between the lines with historical figures, but I can’t see how anyone could question the lesbian identity of Rosa Bonheur.

Wonderful article, beautifully told and amply illustrated. Until today I knew nothing of Rosa Bonheur and I really should have so thank you, Strange Flowers.

Thank you Nina, it’s always a pleasure to see you here.

Can’t believe I had never heard of her – until now! Receiving a new Strange Flowers post in my inbox always give me a lift!

Thanks for your comment; she was unknown to me too until a couple of years ago, but it’s certainly a story worth revisiting!

Hey mate, just wanted to repeat the praise of Nina and crackerneck. Wonderful post. I’m relatively new to your blog having come across it during your 2021 year in review book list, and I’ve recently also purchased a Rixdorf edition, which I hope to read soon. Keep up the excellent work my friend. It’s always a pleasure reading your posts.

Thanks for the comment! It’s always gratifying to see new readers here.

Fascinating post. As always!

Your articles are ever-refreshing !