It’s not every day you get to publish your first two literary translations through your own small press but today – for me – is that day…

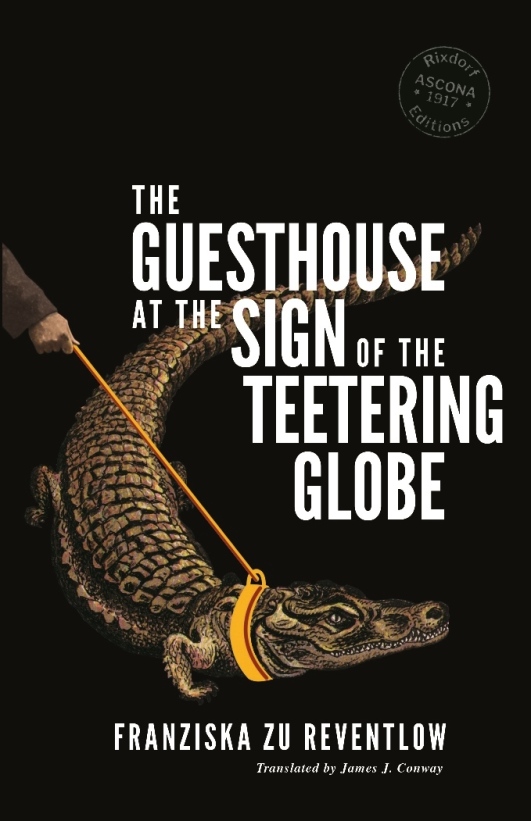

I am thrilled to be propelling these two neglected works into a slightly wider world. They are: Franziska zu Reventlow’s fiction collection The Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe (originally published in 1917) and Magnus Hirschfeld’s 1904 report from the gay and lesbian underground in the German capital around the beginning of the 20th century, Berlin’s Third Sex. You can purchase or order them through good bookstores in the UK or Ireland, or online from Rixdorf Editions.

And for your loyalty and patience, dear Strange Flowers reader, I offer this exclusive excerpt from one of the Reventlow stories:

The Polished Little Man (extract)

The polished little man appeared in our midst one day; later we couldn’t remember exactly when or under what circumstances.

We were stuck in a little Oriental town, bored to death. Each of us had arrived there for a different reason and each was unable to move on for a different reason again.

We spent our time in horrendous boredom and constantly making new chance acquaintances whom we soon discarded because they were annoying and even more boring than ourselves. And that we couldn’t abide. So our circle always came back to its original number of five, and out of sheer apathy we grew even closer to each other, became more inseparable than ever. Gradually it seemed like we would never be able to separate from each other at all. As time went on we forgot that in fact we had been desperate to get away from the two-bit town, forgot what it was we were doing there and gave it no more thought. The hotel where we were staying had become a home to us, and sometimes we seriously considered ending our days there together.

We would most certainly not have indulged the polished little man for so long if we had been a little more vital, rather we would have cast him aside long before. But he must have introduced to our affairs some nuance that had become indispensable to us. And perhaps we needed the audience. Or perhaps we had a vague feeling that if anything were to happen at all, that it would only happen through the polished little man.

In fact he vexed us beyond measure; he was constantly hopping in and out of our midst, surprising us on the most improbable occasions and at the most inopportune moments, perpetually possessed of intolerably good cheer that brought us to the end of our tether, with a shrill squeaky voice that often leapt into the falsetto, giggling incessantly with or without due cause – in short, he was absolutely unbearable. Perhaps this was precisely what attracted us.

It was only when he acquired his name that we began to appreciate him and to regard him as indispensable. At the beginning he was just there – he must have hypnotised us with his polish from the outset, but we had never agreed upon it, never assimilated it into our overall awareness.

But then came the great day. Doctor König hadn’t yet shown, the rest of us had long been sitting in the café, copying Turkish letters from the newspaper and wondering whether one might be able to obtain a Turkish passport for oneself. But these letters were no good to anyone, even a Turk who could speak Turkish. Then along came König – he had been out for a walk alone which may have accounted for his uncharacteristically high spirits. And so it transpired that he posed the momentous question – ‘Why isn’t the polished little man here yet?’.

We breathed a sigh of relief; it had been so long since we were able to jest. And we had already had enough of the unpleasant little man, we were already planning to get rid of him like all our other acquaintances, but now we felt that we needed him, as though we had only just discovered him. König discovered him the moment he named him the polished little man. It was a gift – we felt enriched, inspired.

Half an hour later the polished little man himself came along, and we looked at him properly for the first time. He was fairly short and had bow legs, or rather only one was truly bow, the other merely bandy. The polished little man was very good at concealing it, first stepping forward with the merely bandy leg and then swiftly swinging the truly bow leg behind it. This lent him a peculiar, frisky, hopping gait, and one could tell that he himself believed everything to be shipshape. Moreover, everything about the little man was bright and shiny. His clothes shimmered, the tips of his boots sparkled, his rosy skin looked as though it were freshly coated every day, and every curve – forehead, nose, cheekbones, chin, wrists and every single knuckle – appeared freshly polished. He wore golden glasses which he gently and deftly clasped behind his bright ears, and his pale blue eyes peered brightly through the oval lenses.

Now here he was under the tented roof of the café, and even in our somnolence we couldn’t suppress a faint smile. Even Mrs von B., ordinarily so profound and little given to laughter, let out a bright squeak.

It was difficult to say whether the polished little man had taken note of our merriment, but the weight of probability suggested he must have, for we rarely laughed.

It was a downright uncanny moment, like the dead in the morgue suddenly smiling as one, and one emitting a loud squeak. But the little man paid no mind, which was uncanny enough in itself. Anyone else would have remarked upon our aberrant mirth. We all felt a shiver; the polished little man must have seen right through us, he treated us as though we truly were dead, he must have known that in fact we were no longer capable of laughter, that it was just some superfluous reflex motion.

And certainly it was nothing more than that, and we were immediately earnest again, and returned to the order of the day. In the hotel garden we played tennis. Apart from the scores not a word was spoken. The polished little man hopped and issued orders as usual – we all played very poorly, with no application. Later, at dinner, he assumed his customary seat at the other end of the table amid the strangers with whom we had no contact and who frequently changed, and he recounted anecdotes of exotic royalty and persons of high standing in his customary hushed tones, every inch the tactful diplomat. As usual the anecdotes were deathly dull, and we already knew them anyway, but we listened attentively as we did every evening. Just as we went out onto the street to take our usual evening stroll and visit the café, a man went by carrying a long, quivering iron bar on his shoulder. Mightily alarmed, we recoiled. But Mrs von B., who was a little ahead of us, hit her head on the iron bar and sustained an injury to her forehead. It appeared she hadn’t seen a thing…

James a very interest style. The descriptions are stylized and interesting. Reminds me a little of Jig Saw.

I wonder if you have come across Lionel Gossman’s “Brown Shirt Princess;A study of the Nazi Conscience.”An in depth study of Princess of Marie Adelaide of Lippe-Biesterfeld? Available as PDF.

On Mon, Nov 6, 2017 at 1:05 PM, Strange Flowers wrote:

> James J. Conway posted: “It’s not every day you get to publish your first > two literary translations through your own small press but today – for me – > is that day… I am thrilled to be propelling these two neglected works > into a slightly wider world. They are: Franziska zu Rev” >

No that’s a new one on me I have to say.

First off, many congratulations! I’ve learned so much and have really enjoyed reading Strange Flowers since stumbling across its pages in 2013! The Rixdorf Editions excerpts are fantastic and I’m wondering…will the books be made available in the US? And, please do report on the Nov. 9 launch for those of us “across the pond.” Cheers!

Thanks for your kind words! Rixdorf is hopefully expanding its empire to the US next year. Meanwhile you can buy directly online from the website.

That’s great news, thank you!

Love the translation. Very…polished, indeed.

I’m glad you enjoy!

Sold! I know what I’ll be seen reading next on the S-Bahn! Looking forward to finding out what happens with that polished little man….

Pingback: Secret Satan book list | Strange Flowers

Pingback: Privates on parade | Strange Flowers

Pingback: Franziska zu Reventlow (1871-1918) | Strange Flowers