A third and final dispatch from Prague takes us to the riverside Museum Kampa, gleaming lunar white in the early autumn sun on a stretch of Malá Strana south of the Charles Bridge. A former mill, it was repurposed as a gallery of 20th century art after the Velvet Revolution by Meda Mládek. Her championing of modern Czech art began long before; as well as collecting some of its finest examples with her husband Jan, in 1953 she published a book which featured contributions by André Breton, Jindřich Heisler and Benjamin Péret. This was the first monograph dedicated to the artist whose work we are here to see: Marie Čermínová, better known as Toyen.

Born in Prague in 1902, Toyen studied art before meeting Jindřich Štyrský and joining forces with Devětsil, a uniquely Czech movement combining art and literature. Moving to Paris in the late 1920s, she and Štyrský founded their own movement of two, Artificialism, although it was soon apparent that their vision had considerable crossover with Surrealism. The opportunities that the movement offered women, conditional though they were, Toyen grabbed with both hands. She was anointed by the Surrealist curia. For André Breton, Toyen’s work was “as luminous as her own heart yet streaked through by dark forebodings”.

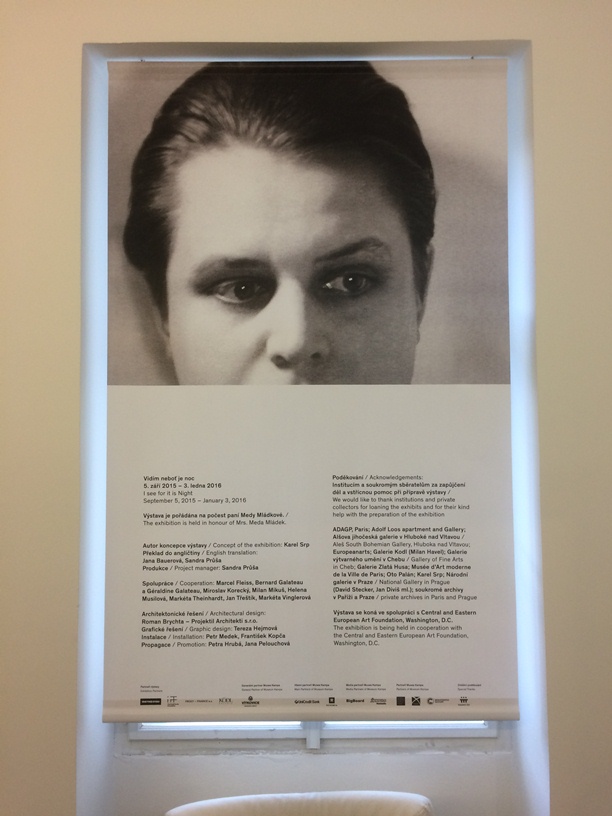

In 1934 Toyen co-founded the Czech Group of Surrealists, and took part in numerous international shows, including the famous 1936 London exhibition in a period which produced some of her most emblematic work, including Sleeper (1937). Despite the arresting figure she presented with her severe, slicked-back hair and workman’s overalls, she was intensely private. Toyen remained in Prague during the brutal Nazi occupation, sheltering Jewish artist Jindřich Heisler in her Žižkov apartment; Štyrský died in 1942. With the Soviets assuming control of what was then Czechoslovakia after the war, Toyen returned to Paris. Her last exhibition during her lifetime united her works with those of the late Štyrský in Brno, shortly before the Prague Spring. However Toyen remained productive right up to her death in 1980. To this day she remains one of the least-known of the major Surrealist artists, although an extensive exhibition in Prague at the beginning of the millennium established her reputation in her homeland, at least.

There are portents, some apparent, some not. Although I was unaware of it at the time, the previous night’s wanderings had led me straight past the block where Heisler waited out the war in Toyen’s apartment. I couldn’t miss Toyen’s Sleeper on posters all over town, little eruptions of mystery amid the everyday, justifying Prague’s reputation as a city whose oddities are brought to the fore. It is a concept explored at length in Derek Sayer’s 2013 book Prague, Capital of the Twentieth Century: A Surrealist History (thanks to Jay for the tip). It opens with André Breton’s 1935 visit to the city, and Toyen features extensively throughout:

According to her own account Marie Čermínová’s nom de plume Toyen was a contraction of the French revolutionary salutation citoyen, though Jaroslav Seifert tells a different story, claiming that he made the name up one day in the National Café. “She was a kind and fine girl,” he says. “We all liked her,” even if “she spoke only in the masculine gender” which “at the beginning we found a little unaccustomed and grotesque, but in time we got used to it.” […] Toyen adopted masculine attire as well as a male grammatical persona, bending gender further than Marcel Duchamp’s occasional feminine alter ego Rrose Selavie ever did.

And the exhibition? Well, edited down to just four modestly sized rooms, the selection from almost six decades’ worth of creativity is inevitably a mere précis. After some naive 1920s juvenilia, the show settles into its focus on Toyen’s classic canvases of ambiguous dreamscapes vaguely delimited by strié washes and inhabited by a familiar Surrealist inventory: lips, hands, birds, gloves, bones, leaves, fish, hair, corsetry, statuary. They tell of anticipation and frustration with a bass note of sexualised menace. The thin, mechanical hum in the room seemed to exude from the paintings themselves rather than the museum’s air conditioning. Physiological anxieties recur – disintegration, slackening, hollowing out. The more abstract works indicate why Toyen was reluctant to give herself entirely to Surrealism, their dynamism more redolent of the Abstract Expressionism to come than many of the more formal non-figurative exercises of between-the-wars painting.

With illusion no longer an option, the post-war works are darker in both palette and sentiment. We are certainly a long way from the whimsical early canvases we left behind just two rooms ago. A 1955 work anticipates Anselm Kiefer, with a crisp, gloved hand gesturing towards a dim enfilade of portals together circumscribing a space at once claustrophobic and immense. Sadly there is almost nothing of Toyen’s works on paper beyond a pair of Max Ernst-inspired collages. Her later experiments in the medium are far more spirited and original, while her line drawings are among the best Surrealism has to offer. Her pansexual erotica, in particular, is exuberant, vital and unabashed, offering some particularly NSFW moments in Sayer’s book. Here, however, there are only oblique references, like the swelling sacs in Larva (1934). The last exhibit is a copy of Mládek’s rare volume, its beige cover disrupted by the lascivious red of the title, one more portent…

Back in the courtyard, it slowly dawns on me that the distinguished looking older woman I had seen in the outdoor café earlier was, in fact, the book’s publisher and the museum’s founder, Meda Mládek (or Mládková), now 96. She is still there, sitting in the sun, and graciously indulges a few moments of my babbling and request for a photo.

That night, on the train back to Berlin: a perigee moon hangs low, picking out the fir-fringed crags looming over the Elbe Valley and the quicksilver ribbon of the river flicking in and out of sight, the night a Toyen-esque hush of expectation.

Thank you for this.

You’re welcome!

Funnily enough, “little eruptions of mystery amid the everyday” perfectly describe how I view every new Strange Flowers post (although after “mystery,” I would add “and wonderment” as well). Regardless of what is happening in the non-internet world, your blog feels like an opulent bohemian oasis where I can meet fascinating new people or reacquaint myself with beloved old friends. I know, I know, to be properly bohemian, it really couldn’t be opulent, but I’m envisioning something along the lines of a party thrown by Stephen Tennant… 🙂

Such kind words! I love the idea of an opulent bohemian oasis. Our garret will be lined with ocelot! Or fauxcelot.

Pingback: Secret Satan, 2019 | Strange Flowers

Pingback: 20 books for 2020 | Strange Flowers

Pingback: Secret Satan, 2020 | Strange Flowers

I enjoyed this very much! You captured her essence.

In June 1977 I went frequently to the Galerie Andre Francois Petit in Paris, where I went to see an exhibition of Tanguy gouaches. One day hen I was there, alone as usual, just before noon, in walked a man in a dark brown heavy suit, short, and with a hat, on the arm of a very chic slender lady wearing a matching skirt and blouse and short jacket in turquoise with a large matching hat and veil. Slowly they went around the gallery inspecting very closely the Tanguy gouaches, and then around the gallery again. The lady with whom I used to converse in Italian who sat at the front desk got up and left and disappeared behind a door. It then suddnely hit me that the two people with whom I was alone in gallery wereToyen on the arm of Annie Le Brun. Out from the door in the back wall behind the desk came Andre Francois Petit and with much bowing and holdng the hand of Toyen, he greeted them,. Then they went over to where one could sign the visitors’ book and wrote their names. Then they left. I went and wrote my name next to theirs. Later, Patrick Waldberg, of whom I was seeing a lot in those days, said to me that I was VERY lucky to have seen Toyen, because “she never goes out, no one ever sees her,” adding that “she looks like a truck driver.” But for Yves Tanguy she came out! It is a memory I have retained ever since, as if it happened yesterday.